Penicillin: The ‘Lucky’ Discovery to Fight Bacterial Infections

This essay was a project of one of the R3 class series I took. Please do not consider it as medical advice.

Defined as naturally occurring or synthesized molecules that fight bacterial infections, antibiotics are one of the most important tools we owe to fight against infectious diseases. The discovery of the first antibiotic in the world - penicillin - by Sir Alexander Fleming in 1928 was a groundbreaking scientific discovery in the fields of medicine and microbiology, and it is also a well-renowned example of serendipity in scientific research – a ‘lucky discovery’.

In the past, infectious diseases like smallpox, pneumonia, and tuberculosis were a severe health threat to people, and had accounted for high mortality and morbidity rates. Bloodletting was once the standard treatment for infectious disease, and during the American civil war, topical iodine and mercury-contained compounds were used to treat wounds. After the discovery of Koch’s Postulates in the late 19th century, scientists came to know that microorganisms are the cause of infectious diseases. However, due to a lack of efficient treatments, infectious diseases remain accounting for high mortality worldwide.

Penicillin was discovered in 1928, purified in 1942, and made widely available in the military in 1945. A golden era of antibiotic discovery followed from the 1950s to the 1970s. Since then, antibiotics have saved countless lives in clinics, and they also served as efficient treatment and prevention methods in agriculture. The discovery of antibiotics revolutionized the field of medical sciences. Even though antibiotic resistance has become a worldwide problem, antibiotics remain widely used in agriculture and clinics nowadays.

Fleming and the Discovery of Penicillin

Before the discovery of penicillin, Fleming was interested in leukocytes’ ability to destroy bacteria. During 1914-1918, Fleming studied septic wounds and noticed that the chemical antiseptics used that time were more efficient when destroying leukocytes than bacteria, thus making them inefficient treatment to bacterial infections.

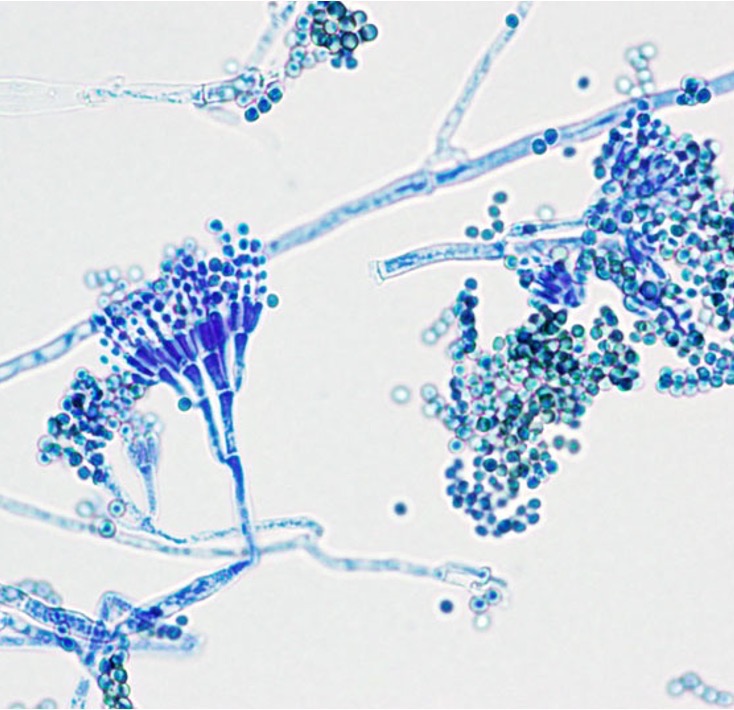

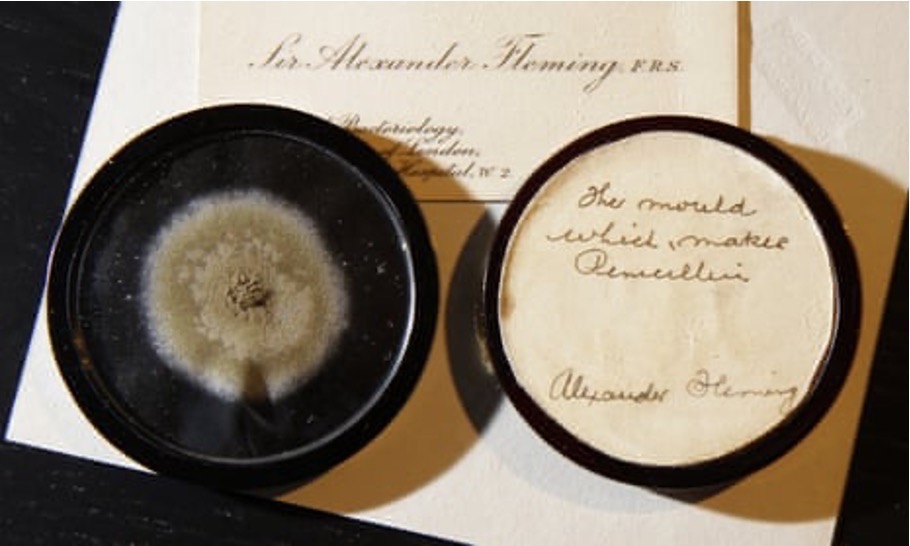

In September 1928, Fleming was working on the variations of staphylococcus colonies at St. Mary’s Hospital Medical School, and he examined the culture plates with staphylococci with a dissecting microscope, which involved in a temporary removal of the cover, so that the colonies were exposed to the contaminants in the air. Fleming noticed that one unexpected mold colony has developed in one of the culture plates, and a substantial number of staphylococcal colonies around the mold colony underwent lysis – ‘what had originally been a well-grown staphylococcal colony was now a faint shadow of its former self’.

Fleming then transferred the mold to a culture tube to grow it and found the culture fluid still showed a remarkable antiseptic power. He grew the penicillin mold with a nutrient broth and found that ‘the culture fluid diluted some 500 to 800 times would completely inhibit the growth of staphylococci’, which is 2 to 3 times more efficient as carbolic acid, the chemical antiseptics used at that time. He also developed a qualitative assay to test the difference in the antibacterial ability of penicillin on various kinds of bacteria, which enables him to find the bacteria species that are most susceptible to penicillin (e.g., Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Pneumococcus, Gonococcus). Later, he pointed out that penicillin’s antibacterial effect is limited to gram-positive pathogens. Fleming’s research was reproduced at the Oxford University to isolate the antibiotics. Since the mold belongs to the genus Penicillium, Fleming named the formerly unknown antiseptic substance ‘penicillin’.

A noticeable ‘risk’ of Fleming’s work is that the introduction of mold is unintentional - it might be attributed to luckiness. However, Fleming admitted that his background in antiseptics and leukocytes was extremely helpful for him to notice the unexpected change in culture plates.

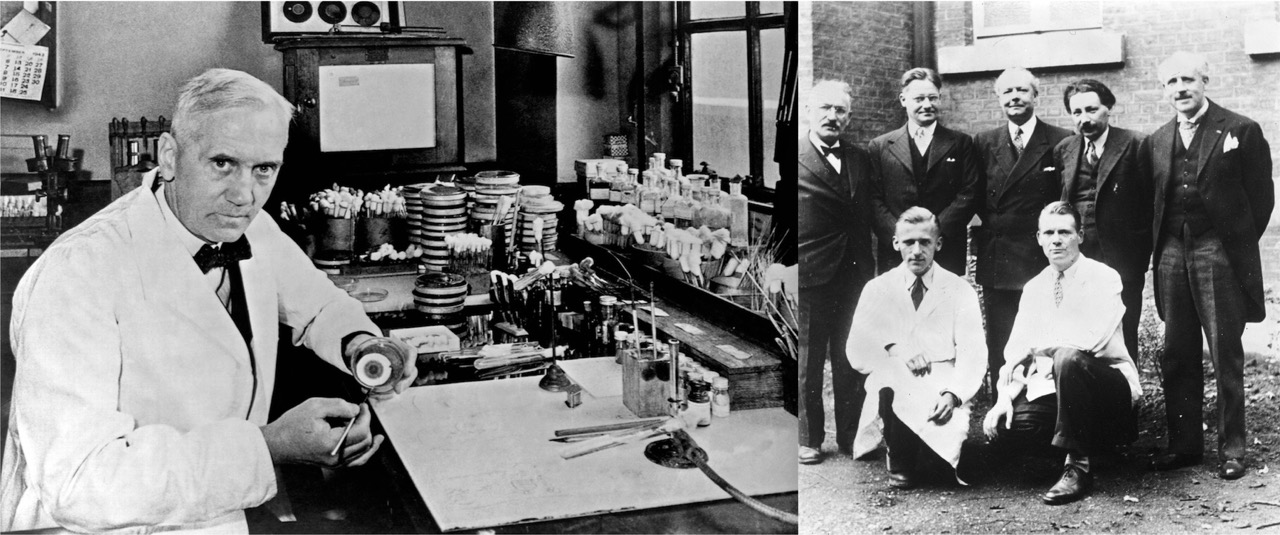

However, Fleming’s discovery hasn’t got much notice at first, since he was not able to purity the substance or test its antiseptic strength against bacterial infections in humans or animals. Those steps were made possible by the Oxford penicillin team led by Howard Florey, a pathology professor at the Sir William Dunn School at Oxford, and his fellows including Ernst Chain and Norman Heatley. From 1939 to 1941, the team successfully purified the substance, developed methods for large-scale isolation and production, and carried out the first mouse and human trails of penicillin treatment.

In 1945, Fleming, Florey and Chain together won the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine for the discovery and use of the antibiotic agent, which since then had saved millions of lives.

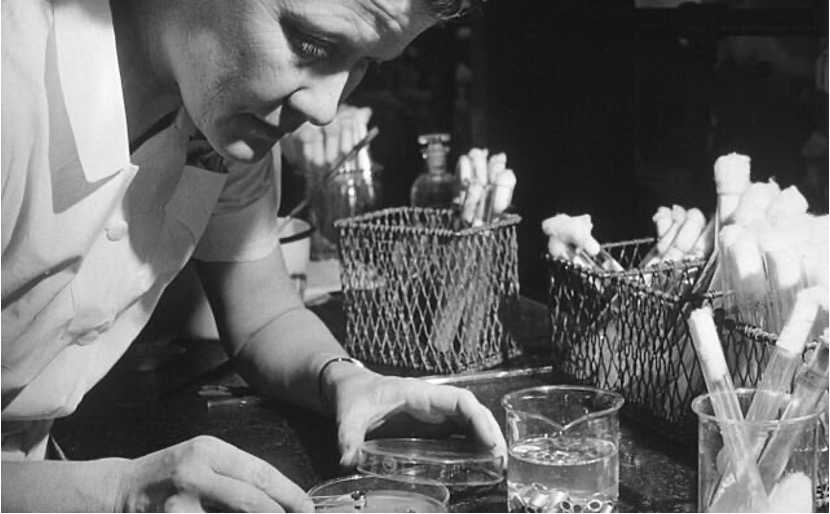

Ignored Contributers

Shortly after the discovery of penicillin, the discovery, isolation, and purification of the broad-spectrum antibiotic streptomycin was made possible by the Waksman lab at Rutgers University. Waksman was given the 1952 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology. However, several female researchers who contributed greatly to the program were barely mentioned in this story, including E. S. Horning, who developed an efficient screening protocol to isolate soil microbes and E. J. Bugie, who collaborated in the streptomycin discovery paper but got her name removed for the patent. At that time, women in science were underrepresented - their contributions to the projects were intentionally ignored, not to mention that their role as strong supporters for their husbands are usually overlooked.

The Impact of Antibiotics

The discovery of penicillin and many other antibiotics have saved countless lives on this planet. After WWII, war-time innovations including antibiotics were used to fight against infectious disease globally. For example, people found that a combination of antibiotics can cure tuberculosis, which was not possible before WWII. Antibiotics were also used in food production industry to promote growth, prevent infection, and treat diseases of animals and plants, which effectively boosted food production and contributed to the huge global population growth in the later 20th century. Nevertheless, the intensive use of antibiotics over the years have resulted in the prevalence of antibiotic resistance, which has led to increasing concern about its influence on animal and human health. An example would be ‘superbugs’ in the clinics – they are multidrug resistant bacteria strains (e.g., C. difficile) that cannot be simply eliminated by antibiotics.

Antibiotics was one of the most important medical advances in the 20th century, however, due to excessive use, its resistance has become prevalent in nature. In the future, more caution should be given when using antibiotics, and antibiotic resistance surveillance should also receive enough attention from public health organizations.